This Keeps Track of What Files Are Saved and Where Theyã¢â‚¬â„¢are Stored on the Disk

File-System Implementation

References:

- Abraham Silberschatz, Greg Gagne, and Peter Baer Galvin, "Operating System Concepts, Ninth Edition ", Chapter 12

12.1 File-System Structure

- Hard disks have two important properties that make them suitable for secondary storage of files in file systems: (1) Blocks of data can be rewritten in place, and (2) they are direct access, allowing any block of data to be accessed with only ( relatively ) minor movements of the disk heads and rotational latency. ( See Chapter 12 )

- Disks are usually accessed in physical blocks, rather than a byte at a time. Block sizes may range from 512 bytes to 4K or larger.

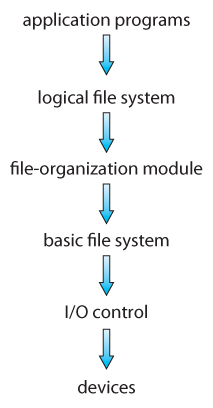

- File systems organize storage on disk drives, and can be viewed as a layered design:

- At the lowest layer are the physical devices, consisting of the magnetic media, motors & controls, and the electronics connected to them and controlling them. Modern disk put more and more of the electronic controls directly on the disk drive itself, leaving relatively little work for the disk controller card to perform.

- I/O Control consists of device drivers , special software programs ( often written in assembly ) which communicate with the devices by reading and writing special codes directly to and from memory addresses corresponding to the controller card's registers. Each controller card ( device ) on a system has a different set of addresses ( registers, a.k.a. ports ) that it listens to, and a unique set of command codes and results codes that it understands.

- The basic file system level works directly with the device drivers in terms of retrieving and storing raw blocks of data, without any consideration for what is in each block. Depending on the system, blocks may be referred to with a single block number, ( e.g. block # 234234 ), or with head-sector-cylinder combinations.

- The file organization module knows about files and their logical blocks, and how they map to physical blocks on the disk. In addition to translating from logical to physical blocks, the file organization module also maintains the list of free blocks, and allocates free blocks to files as needed.

- The logical file system deals with all of the meta data associated with a file ( UID, GID, mode, dates, etc ), i.e. everything about the file except the data itself. This level manages the directory structure and the mapping of file names to file control blocks, FCBs , which contain all of the meta data as well as block number information for finding the data on the disk.

- The layered approach to file systems means that much of the code can be used uniformly for a wide variety of different file systems, and only certain layers need to be filesystem specific. Common file systems in use include the UNIX file system, UFS, the Berkeley Fast File System, FFS, Windows systems FAT, FAT32, NTFS, CD-ROM systems ISO 9660, and for Linux the extended file systems ext2 and ext3 ( among 40 others supported. )

Figure 12.1 - Layered file system.

12.2 File-System Implementation

12.2.1 Overview

- File systems store several important data structures on the disk:

- A boot-control block, ( per volume ) a.k.a. the boot block in UNIX or the partition boot sector in Windows contains information about how to boot the system off of this disk. This will generally be the first sector of the volume if there is a bootable system loaded on that volume, or the block will be left vacant otherwise.

- A volume control block, ( per volume ) a.k.a. the master file table in UNIX or the superblock in Windows, which contains information such as the partition table, number of blocks on each filesystem, and pointers to free blocks and free FCB blocks.

- A directory structure ( per file system ), containing file names and pointers to corresponding FCBs. UNIX uses inode numbers, and NTFS uses a master file table.

- The File Control Block, FCB, ( per file ) containing details about ownership, size, permissions, dates, etc. UNIX stores this information in inodes, and NTFS in the master file table as a relational database structure.

Figure 12.2 - A typical file-control block.

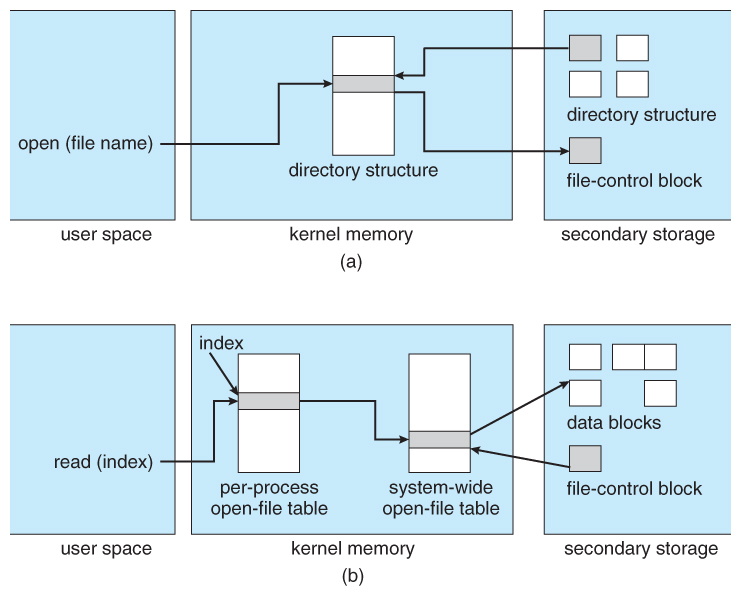

- There are also several key data structures stored in memory:

- An in-memory mount table.

- An in-memory directory cache of recently accessed directory information.

- A system-wide open file table , containing a copy of the FCB for every currently open file in the system, as well as some other related information.

- A per-process open file table, containing a pointer to the system open file table as well as some other information. ( For example the current file position pointer may be either here or in the system file table, depending on the implementation and whether the file is being shared or not. )

- Figure 12.3 illustrates some of the interactions of file system components when files are created and/or used:

- When a new file is created, a new FCB is allocated and filled out with important information regarding the new file. The appropriate directory is modified with the new file name and FCB information.

- When a file is accessed during a program, the open( ) system call reads in the FCB information from disk, and stores it in the system-wide open file table. An entry is added to the per-process open file table referencing the system-wide table, and an index into the per-process table is returned by the open( ) system call. UNIX refers to this index as a file descriptor , and Windows refers to it as a file handle .

- If another process already has a file open when a new request comes in for the same file, and it is sharable, then a counter in the system-wide table is incremented and the per-process table is adjusted to point to the existing entry in the system-wide table.

- When a file is closed, the per-process table entry is freed, and the counter in the system-wide table is decremented. If that counter reaches zero, then the system wide table is also freed. Any data currently stored in memory cache for this file is written out to disk if necessary.

Figure 12.3 - In-memory file-system structures. (a) File open. (b) File read.12.2.2 Partitions and Mounting

- Physical disks are commonly divided into smaller units called partitions. They can also be combined into larger units, but that is most commonly done for RAID installations and is left for later chapters.

- Partitions can either be used as raw devices ( with no structure imposed upon them ), or they can be formatted to hold a filesystem ( i.e. populated with FCBs and initial directory structures as appropriate. ) Raw partitions are generally used for swap space, and may also be used for certain programs such as databases that choose to manage their own disk storage system. Partitions containing filesystems can generally only be accessed using the file system structure by ordinary users, but can often be accessed as a raw device also by root.

- The boot block is accessed as part of a raw partition, by the boot program prior to any operating system being loaded. Modern boot programs understand multiple OSes and filesystem formats, and can give the user a choice of which of several available systems to boot.

- The root partition contains the OS kernel and at least the key portions of the OS needed to complete the boot process. At boot time the root partition is mounted, and control is transferred from the boot program to the kernel found there. ( Older systems required that the root partition lie completely within the first 1024 cylinders of the disk, because that was as far as the boot program could reach. Once the kernel had control, then it could access partitions beyond the 1024 cylinder boundary. )

- Continuing with the boot process, additional filesystems get mounted, adding their information into the appropriate mount table structure. As a part of the mounting process the file systems may be checked for errors or inconsistencies, either because they are flagged as not having been closed properly the last time they were used, or just for general principals. Filesystems may be mounted either automatically or manually. In UNIX a mount point is indicated by setting a flag in the in-memory copy of the inode, so all future references to that inode get re-directed to the root directory of the mounted filesystem.

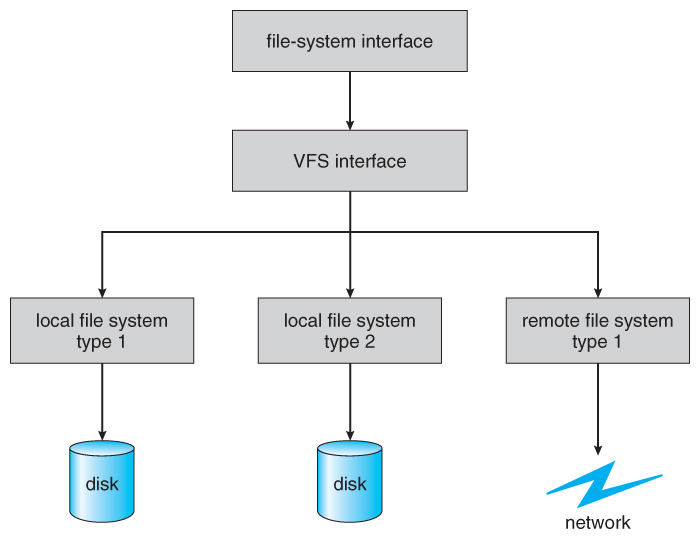

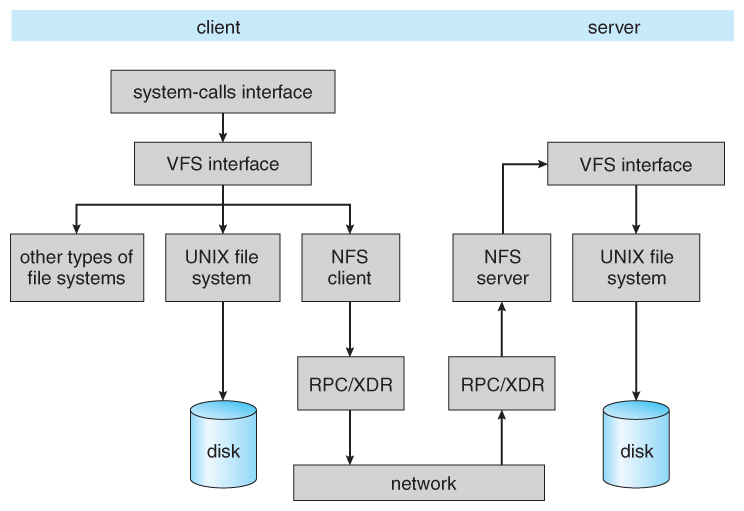

12.2.3 Virtual File Systems

- Virtual File Systems, VFS , provide a common interface to multiple different filesystem types. In addition, it provides for a unique identifier ( vnode ) for files across the entire space, including across all filesystems of different types. ( UNIX inodes are unique only across a single filesystem, and certainly do not carry across networked file systems. )

- The VFS in Linux is based upon four key object types:

- The inode object, representing an individual file

- The file object, representing an open file.

- The superblock object, representing a filesystem.

- The dentry object, representing a directory entry.

- Linux VFS provides a set of common functionalities for each filesystem, using function pointers accessed through a table. The same functionality is accessed through the same table position for all filesystem types, though the actual functions pointed to by the pointers may be filesystem-specific. See /usr/include/linux/fs.h for full details. Common operations provided include open( ), read( ), write( ), and mmap( ).

Figure 12.4 - Schematic view of a virtual file system.

12.3 Directory Implementation

- Directories need to be fast to search, insert, and delete, with a minimum of wasted disk space.

12.3.1 Linear List

- A linear list is the simplest and easiest directory structure to set up, but it does have some drawbacks.

- Finding a file ( or verifying one does not already exist upon creation ) requires a linear search.

- Deletions can be done by moving all entries, flagging an entry as deleted, or by moving the last entry into the newly vacant position.

- Sorting the list makes searches faster, at the expense of more complex insertions and deletions.

- A linked list makes insertions and deletions into a sorted list easier, with overhead for the links.

- More complex data structures, such as B-trees, could also be considered.

12.3.2 Hash Table

- A hash table can also be used to speed up searches.

- Hash tables are generally implemented in addition to a linear or other structure

12.4 Allocation Methods

- There are three major methods of storing files on disks: contiguous, linked, and indexed.

12.4.1 Contiguous Allocation

- Contiguous Allocation requires that all blocks of a file be kept together contiguously.

- Performance is very fast, because reading successive blocks of the same file generally requires no movement of the disk heads, or at most one small step to the next adjacent cylinder.

- Storage allocation involves the same issues discussed earlier for the allocation of contiguous blocks of memory ( first fit, best fit, fragmentation problems, etc. ) The distinction is that the high time penalty required for moving the disk heads from spot to spot may now justify the benefits of keeping files contiguously when possible.

- ( Even file systems that do not by default store files contiguously can benefit from certain utilities that compact the disk and make all files contiguous in the process. )

- Problems can arise when files grow, or if the exact size of a file is unknown at creation time:

- Over-estimation of the file's final size increases external fragmentation and wastes disk space.

- Under-estimation may require that a file be moved or a process aborted if the file grows beyond its originally allocated space.

- If a file grows slowly over a long time period and the total final space must be allocated initially, then a lot of space becomes unusable before the file fills the space.

- A variation is to allocate file space in large contiguous chunks, called extents. When a file outgrows its original extent, then an additional one is allocated. ( For example an extent may be the size of a complete track or even cylinder, aligned on an appropriate track or cylinder boundary. ) The high-performance files system Veritas uses extents to optimize performance.

Figure 12.5 - Contiguous allocation of disk space.12.4.2 Linked Allocation

- Disk files can be stored as linked lists, with the expense of the storage space consumed by each link. ( E.g. a block may be 508 bytes instead of 512. )

- Linked allocation involves no external fragmentation, does not require pre-known file sizes, and allows files to grow dynamically at any time.

- Unfortunately linked allocation is only efficient for sequential access files, as random access requires starting at the beginning of the list for each new location access.

- Allocating clusters of blocks reduces the space wasted by pointers, at the cost of internal fragmentation.

- Another big problem with linked allocation is reliability if a pointer is lost or damaged. Doubly linked lists provide some protection, at the cost of additional overhead and wasted space.

Figure 12.6 - Linked allocation of disk space.

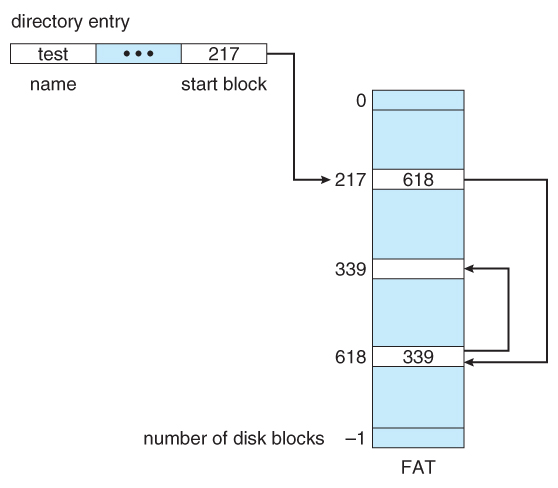

- The File Allocation Table, FAT, used by DOS is a variation of linked allocation, where all the links are stored in a separate table at the beginning of the disk. The benefit of this approach is that the FAT table can be cached in memory, greatly improving random access speeds.

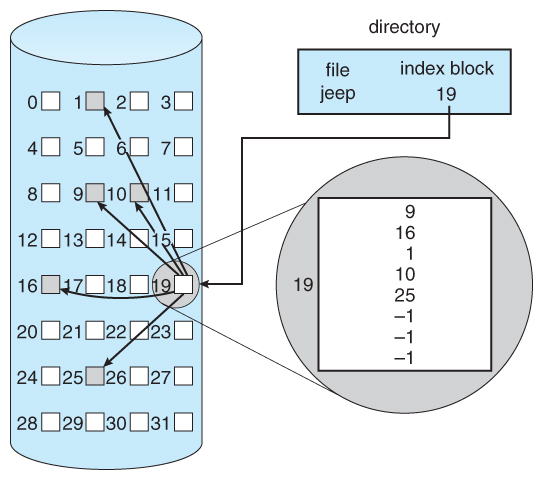

Figure 12.7 File-allocation table.12.4.3 Indexed Allocation

- Indexed Allocation combines all of the indexes for accessing each file into a common block ( for that file ), as opposed to spreading them all over the disk or storing them in a FAT table.

Figure 12.8 - Indexed allocation of disk space.

- Some disk space is wasted ( relative to linked lists or FAT tables ) because an entire index block must be allocated for each file, regardless of how many data blocks the file contains. This leads to questions of how big the index block should be, and how it should be implemented. There are several approaches:

- Linked Scheme - An index block is one disk block, which can be read and written in a single disk operation. The first index block contains some header information, the first N block addresses, and if necessary a pointer to additional linked index blocks.

- Multi-Level Index - The first index block contains a set of pointers to secondary index blocks, which in turn contain pointers to the actual data blocks.

- Combined Scheme - This is the scheme used in UNIX inodes, in which the first 12 or so data block pointers are stored directly in the inode, and then singly, doubly, and triply indirect pointers provide access to more data blocks as needed. ( See below. ) The advantage of this scheme is that for small files ( which many are ), the data blocks are readily accessible ( up to 48K with 4K block sizes ); files up to about 4144K ( using 4K blocks ) are accessible with only a single indirect block ( which can be cached ), and huge files are still accessible using a relatively small number of disk accesses ( larger in theory than can be addressed by a 32-bit address, which is why some systems have moved to 64-bit file pointers. )

Figure 12.9 - The UNIX inode.12.4.4 Performance

- The optimal allocation method is different for sequential access files than for random access files, and is also different for small files than for large files.

- Some systems support more than one allocation method, which may require specifying how the file is to be used ( sequential or random access ) at the time it is allocated. Such systems also provide conversion utilities.

- Some systems have been known to use contiguous access for small files, and automatically switch to an indexed scheme when file sizes surpass a certain threshold.

- And of course some systems adjust their allocation schemes ( e.g. block sizes ) to best match the characteristics of the hardware for optimum performance.

12.5 Free-Space Management

- Another important aspect of disk management is keeping track of and allocating free space.

12.5.1 Bit Vector

- One simple approach is to use a bit vector , in which each bit represents a disk block, set to 1 if free or 0 if allocated.

- Fast algorithms exist for quickly finding contiguous blocks of a given size

- The down side is that a 40GB disk requires over 5MB just to store the bitmap. ( For example. )

12.5.2 Linked List

- A linked list can also be used to keep track of all free blocks.

- Traversing the list and/or finding a contiguous block of a given size are not easy, but fortunately are not frequently needed operations. Generally the system just adds and removes single blocks from the beginning of the list.

- The FAT table keeps track of the free list as just one more linked list on the table.

Figure 12.10 - Linked free-space list on disk.12.5.3 Grouping

- A variation on linked list free lists is to use links of blocks of indices of free blocks. If a block holds up to N addresses, then the first block in the linked-list contains up to N-1 addresses of free blocks and a pointer to the next block of free addresses.

12.5.4 Counting

- When there are multiple contiguous blocks of free space then the system can keep track of the starting address of the group and the number of contiguous free blocks. As long as the average length of a contiguous group of free blocks is greater than two this offers a savings in space needed for the free list. ( Similar to compression techniques used for graphics images when a group of pixels all the same color is encountered. )

12.5.5 Space Maps

- Sun's ZFS file system was designed for HUGE numbers and sizes of files, directories, and even file systems.

- The resulting data structures could be VERY inefficient if not implemented carefully. For example, freeing up a 1 GB file on a 1 TB file system could involve updating thousands of blocks of free list bit maps if the file was spread across the disk.

- ZFS uses a combination of techniques, starting with dividing the disk up into ( hundreds of ) metaslabs of a manageable size, each having their own space map.

- Free blocks are managed using the counting technique, but rather than write the information to a table, it is recorded in a log-structured transaction record. Adjacent free blocks are also coalesced into a larger single free block.

- An in-memory space map is constructed using a balanced tree data structure, constructed from the log data.

- The combination of the in-memory tree and the on-disk log provide for very fast and efficient management of these very large files and free blocks.

12.6 Efficiency and Performance

12.6.1 Efficiency

- UNIX pre-allocates inodes, which occupies space even before any files are created.

- UNIX also distributes inodes across the disk, and tries to store data files near their inode, to reduce the distance of disk seeks between the inodes and the data.

- Some systems use variable size clusters depending on the file size.

- The more data that is stored in a directory ( e.g. last access time ), the more often the directory blocks have to be re-written.

- As technology advances, addressing schemes have had to grow as well.

- Sun's ZFS file system uses 128-bit pointers, which should theoretically never need to be expanded. ( The mass required to store 2^128 bytes with atomic storage would be at least 272 trillion kilograms! )

- Kernel table sizes used to be fixed, and could only be changed by rebuilding the kernels. Modern tables are dynamically allocated, but that requires more complicated algorithms for accessing them.

12.6.2 Performance

- Disk controllers generally include on-board caching. When a seek is requested, the heads are moved into place, and then an entire track is read, starting from whatever sector is currently under the heads ( reducing latency. ) The requested sector is returned and the unrequested portion of the track is cached in the disk's electronics.

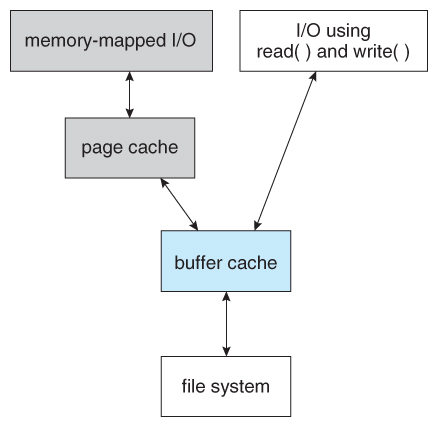

- Some OSes cache disk blocks they expect to need again in a buffer cache.

- A page cache connected to the virtual memory system is actually more efficient as memory addresses do not need to be converted to disk block addresses and back again.

- Some systems ( Solaris, Linux, Windows 2000, NT, XP ) use page caching for both process pages and file data in a unified virtual memory.

- Figures 11.11 and 11.12 show the advantages of the unified buffer cache found in some versions of UNIX and Linux - Data does not need to be stored twice, and problems of inconsistent buffer information are avoided.

Figure 12.11 - I/O without a unified buffer cache.

Figure 12.12 - I/O using a unified buffer cache.

- Page replacement strategies can be complicated with a unified cache, as one needs to decide whether to replace process or file pages, and how many pages to guarantee to each category of pages. Solaris, for example, has gone through many variations, resulting in priority paging giving process pages priority over file I/O pages, and setting limits so that neither can knock the other completely out of memory.

- Another issue affecting performance is the question of whether to implement synchronous writes or asynchronous writes. Synchronous writes occur in the order in which the disk subsystem receives them, without caching; Asynchronous writes are cached, allowing the disk subsystem to schedule writes in a more efficient order ( See Chapter 12. ) Metadata writes are often done synchronously. Some systems support flags to the open call requiring that writes be synchronous, for example for the benefit of database systems that require their writes be performed in a required order.

- The type of file access can also have an impact on optimal page replacement policies. For example, LRU is not necessarily a good policy for sequential access files. For these types of files progression normally goes in a forward direction only, and the most recently used page will not be needed again until after the file has been rewound and re-read from the beginning, ( if it is ever needed at all. ) On the other hand, we can expect to need the next page in the file fairly soon. For this reason sequential access files often take advantage of two special policies:

- Free-behind frees up a page as soon as the next page in the file is requested, with the assumption that we are now done with the old page and won't need it again for a long time.

- Read-ahead reads the requested page and several subsequent pages at the same time, with the assumption that those pages will be needed in the near future. This is similar to the track caching that is already performed by the disk controller, except it saves the future latency of transferring data from the disk controller memory into motherboard main memory.

- The caching system and asynchronous writes speed up disk writes considerably, because the disk subsystem can schedule physical writes to the disk to minimize head movement and disk seek times. ( See Chapter 12. ) Reads, on the other hand, must be done more synchronously in spite of the caching system, with the result that disk writes can counter-intuitively be much faster on average than disk reads.

12.7 Recovery

12.7.1 Consistency Checking

- The storing of certain data structures ( e.g. directories and inodes ) in memory and the caching of disk operations can speed up performance, but what happens in the result of a system crash? All volatile memory structures are lost, and the information stored on the hard drive may be left in an inconsistent state.

- A Consistency Checker ( fsck in UNIX, chkdsk or scandisk in Windows ) is often run at boot time or mount time, particularly if a filesystem was not closed down properly. Some of the problems that these tools look for include:

- Disk blocks allocated to files and also listed on the free list.

- Disk blocks neither allocated to files nor on the free list.

- Disk blocks allocated to more than one file.

- The number of disk blocks allocated to a file inconsistent with the file's stated size.

- Properly allocated files / inodes which do not appear in any directory entry.

- Link counts for an inode not matching the number of references to that inode in the directory structure.

- Two or more identical file names in the same directory.

- Illegally linked directories, e.g. cyclical relationships where those are not allowed, or files/directories that are not accessible from the root of the directory tree.

- Consistency checkers will often collect questionable disk blocks into new files with names such as chk00001.dat. These files may contain valuable information that would otherwise be lost, but in most cases they can be safely deleted, ( returning those disk blocks to the free list. )

- UNIX caches directory information for reads, but any changes that affect space allocation or metadata changes are written synchronously, before any of the corresponding data blocks are written to.

12.7.2 Log-Structured File Systems ( was 11.8 )

- Log-based transaction-oriented ( a.k.a. journaling ) filesystems borrow techniques developed for databases, guaranteeing that any given transaction either completes successfully or can be rolled back to a safe state before the transaction commenced:

- All metadata changes are written sequentially to a log.

- A set of changes for performing a specific task ( e.g. moving a file ) is a transaction .

- As changes are written to the log they are said to be committed, allowing the system to return to its work.

- In the meantime, the changes from the log are carried out on the actual filesystem, and a pointer keeps track of which changes in the log have been completed and which have not yet been completed.

- When all changes corresponding to a particular transaction have been completed, that transaction can be safely removed from the log.

- At any given time, the log will contain information pertaining to uncompleted transactions only, e.g. actions that were committed but for which the entire transaction has not yet been completed.

- From the log, the remaining transactions can be completed,

- or if the transaction was aborted, then the partially completed changes can be undone.

12.7.3 Other Solutions ( New )

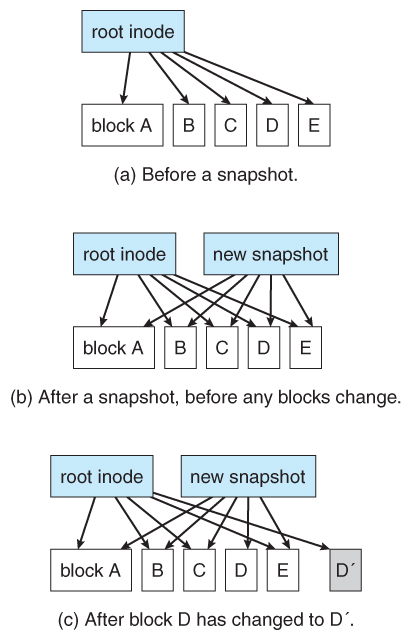

- Sun's ZFS and Network Appliance's WAFL file systems take a different approach to file system consistency.

- No blocks of data are ever over-written in place. Rather the new data is written into fresh new blocks, and after the transaction is complete, the metadata ( data block pointers ) is updated to point to the new blocks.

- The old blocks can then be freed up for future use.

- Alternatively, if the old blocks and old metadata are saved, then a snapshot of the system in its original state is preserved. This approach is taken by WAFL.

- ZFS combines this with check-summing of all metadata and data blocks, and RAID, to ensure that no inconsistencies are possible, and therefore ZFS does not incorporate a consistency checker.

12.7.4 Backup and Restore

- In order to recover lost data in the event of a disk crash, it is important to conduct backups regularly.

- Files should be copied to some removable medium, such as magnetic tapes, CDs, DVDs, or external removable hard drives.

- A full backup copies every file on a filesystem.

- Incremental backups copy only files which have changed since some previous time.

- A combination of full and incremental backups can offer a compromise between full recoverability, the number and size of backup tapes needed, and the number of tapes that need to be used to do a full restore. For example, one strategy might be:

- At the beginning of the month do a full backup.

- At the end of the first and again at the end of the second week, backup all files which have changed since the beginning of the month.

- At the end of the third week, backup all files that have changed since the end of the second week.

- Every day of the month not listed above, do an incremental backup of all files that have changed since the most recent of the weekly backups described above.

- Backup tapes are often reused, particularly for daily backups, but there are limits to how many times the same tape can be used.

- Every so often a full backup should be made that is kept "forever" and not overwritten.

- Backup tapes should be tested, to ensure that they are readable!

- For optimal security, backup tapes should be kept off-premises, so that a fire or burglary cannot destroy both the system and the backups. There are companies ( e.g. Iron Mountain ) that specialize in the secure off-site storage of critical backup information.

- Keep your backup tapes secure - The easiest way for a thief to steal all your data is to simply pocket your backup tapes!

- Storing important files on more than one computer can be an alternate though less reliable form of backup.

- Note that incremental backups can also help users to get back a previous version of a file that they have since changed in some way.

- Beware that backups can help forensic investigators recover e-mails and other files that users had though they had deleted!

12.8 NFS ( Optional )

12.8.1 Overview

Figure 12.13 - Three independent file systems.

Figure 12.14 - Mounting in NFS. (a) Mounts. (b) Cascading mounts.12.8.2 The Mount Protocol

- The NFS mount protocol is similar to the local mount protocol, establishing a connection between a specific local directory ( the mount point ) and a specific device from a remote system.

- Each server maintains an export list of the local filesystems ( directory sub-trees ) which are exportable, who they are exportable to, and what restrictions apply ( e.g. read-only access. )

- The server also maintains a list of currently connected clients, so that they can be notified in the event of the server going down and for other reasons.

- Automount and autounmount are supported.

12.8.3 The NFS Protocol

- Implemented as a set of remote procedure calls ( RPCs ):

- Searching for a file in a directory

- REading a set of directory entries

- Manipulating links and directories

- Accessing file attributes

- Reading and writing files

Figure 12.15 - Schematic view of the NFS architecture.12.8.4 Path-Name Translation

11.8.5 Remote Operations

- Buffering and caching improve performance, but can cause a disparity in local versus remote views of the same file(s).

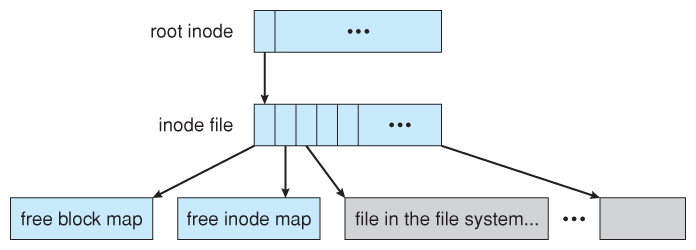

12.9 Example: The WAFL File System ( Optional )

- Write Anywhere File Layout

- Designed for a specific hardware architecture.

- Snapshots record the state of the system at regular or irregular intervals.

- The snapshot just copies the inode pointers, not the actual data.

- Used pages are not overwritten, so updates are fast.

- Blocks keep counters for how many snapshots are pointing to that block - When the counter reaches zero, then the block is considered free.

Figure 12.16 - The WAFL file layout.

Figure 12.17 - Snapshots in WAFL

12.10 Summary

This Keeps Track of What Files Are Saved and Where Theyã¢â‚¬â„¢are Stored on the Disk

Source: https://www.cs.uic.edu/~jbell/CourseNotes/OperatingSystems/12_FileSystemImplementation.html

0 Response to "This Keeps Track of What Files Are Saved and Where Theyã¢â‚¬â„¢are Stored on the Disk"

Enregistrer un commentaire